BENJAMIN FRANKLIN had not heard of Mossack Fonseca when he observed “nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes,” and the Panama-based law firm might have changed his mind. Mossack is at the centre of a huge tax and money-laundering scandal, now coming to light thanks to the so-called “Panama papers”. What exactly are these papers and why do they matter?

Companies such as Mossack specialise in helping foreigners hide wealth. Clients may want to keep money away from soon-to-be ex-wives, dodge sanctions, launder money or evade taxes. The main tools for doing so are anonymous shell companies (which exist only on paper) and offshore accounts in tax havens (which often come with perks such as banking secrecy and low to no taxes). These structures obscure the identity of the true owner of money parked in or routed through jurisdictions such as Panama.

Advertisement

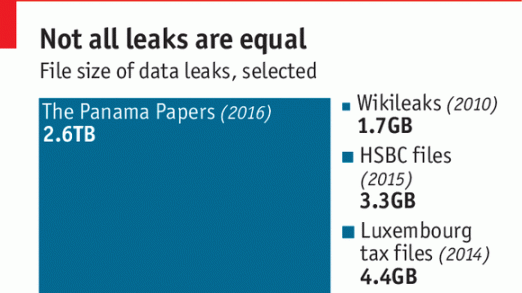

But authorities (and disgruntled ex-wives) just caught a break. Over 11m documents have been leaked from Mossack’s secretive offices. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) this weekend went public with its findings that the firm had, wittingly or unwittingly, helped clients evade or avoid tax, launder money or mask its origins. More astonishing than their methods, which are well known, was the scale of activity and the people involved. The 2.6 terabytes of data are thought to contain information about 214,500 companies in 21 offshore jurisdictions and name over 14,000 middlemen (such as banks and law firms) with whom the law firm has allegedly worked. Although by no means all of these are criminal or even shady, the first public examples make for telling reading. On the naughty list are people such as Ukraine’s president, Petro Poroshenko, who promised to sell his business interests on taking office. He seems to have merely transferred assets to an offshore shell. Other heads of government, such as Russia’s Vladimir Putin and Iceland’s Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson are suspected of hiding ownership of offshore assets by putting them in the names of friends or relatives. Mossack denies any wrongdoing, as does Mr Gunnlaugsson. A spokesman for Mr Putin has denounced the allegations as a case of “Putinophobia”.

After the initial naming and shaming, it will become clearer in the coming weeks who was using these structures for dodgy reasons. While examples of the offshore industry enabling dictators, terrorists and drug cartels will (rightly) capture much of the attention, it would be a shame if other miscreants escape. The global industry of service providers, which sell financial secrecy to those who can afford it, have in some cases done more than just feast on poorly designed tax policies. The Panama documents suggest that some actively looked the other way when faced with a less-than-clean client. An estimated 8% of the world’s wealth ($7.6 trillion according to Gabriel Zucman, an economist) is stuffed away in offshore accounts, most of it done perfectly legally, as a raft of public relations people hasten to say as their clients’ names are flung around in the press. But legal or not, the newspapers taking aim at Mossack and the like will strike a chord. They are in tune with contemporary sentiment: the fundamental disconnect between global elites and the rest, for whom taxes are as certain as death.